So, you have an idea for a medical device, and you obviously want to take it to the market so that it can have a positive impact on tons of people’s lives and maybe make you a little money as well.

Maybe you’ve been working in the lab, iterating on this device. Maybe you’ve tested it on a mouse. Maybe done some bench testing. The things seem to work, so now you really want to move forward with this product.

There’s a laundry list of things you’ll need to do to start a medical device company, just like any business. And quite a few decisions to make: Do I LLC or Inc? What’s director’s insurance? Do I need it? What’s my company name? What next…for design? How do I get this to market?

And now, you’re probably excited. Perhaps a little overwhelmed. Perhaps somewhat lost. You feel like this thing is ready for primetime, but you’re going to have to slow down…because you’re now moving out of ideation and R&D into industry. And this industry is a regulated space.

One of the first regulations you’ll need to become familiar with is the quality regulations. The quality regulations are essentially regulations on how to run the various areas of your business that impact the final product—your device. These regulations cover items like design, management responsibility, document control, record control, change control, and so on. There are various quality regulations and standards for different regulatory agencies, but here, we’ll start with FDA and their quality system regulation: 21CFR 820. In particular, we’re going to focus on Design Controls (21CFR 820.30). We’ll touch upon the other sections in other articles.

Purpose & General History of Design Controls:

So, what’s all this talk about design controls for? What is it? Why is it necessary?

Design Controls began when the FDA authorized the Safe Medical Device Act of 1990 to expand the scope of current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) to impose more control over the development process of medical devices. The intention was to avoid uncontrolled changes during the design process and afford more predictability to ultimately avoid previously unforeseen problems.

Let’s equate this to another potentially familiar topic: writing a speech or essay. First you come with a high-level outline. Then you fill in the sub bullets of the outline. Then you write the paper. The intention is to keep you focused, concise, and clear, avoiding errors, rabbit holes, and incoherent babble. You’re planning in the early stages and then fleshing out the details further and further until you have a final, stellar piece of work, deserving of a Pulitzer (or at least a passing grade).

Similarly, the general purpose of design controls is to ensure that a suitable plan is in place for the development and production of a product.

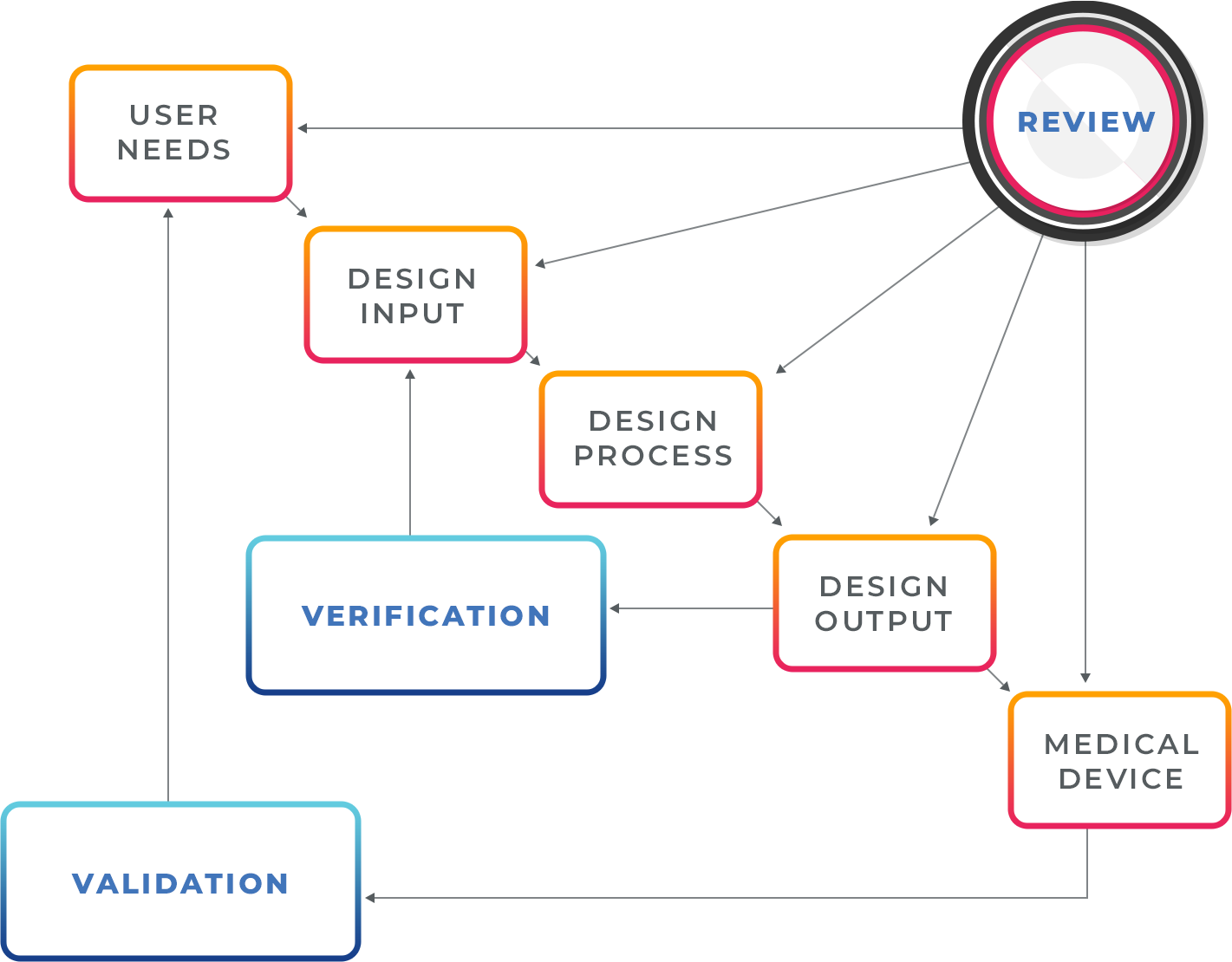

The design control process for medical devices breaks down into 5 general sections which are typically outlined in a design matrix and/or other documentation. These 5 sections are:

- User Needs

- Design Input

- Design Output

- Design Verification

- Design Validation

User Needs

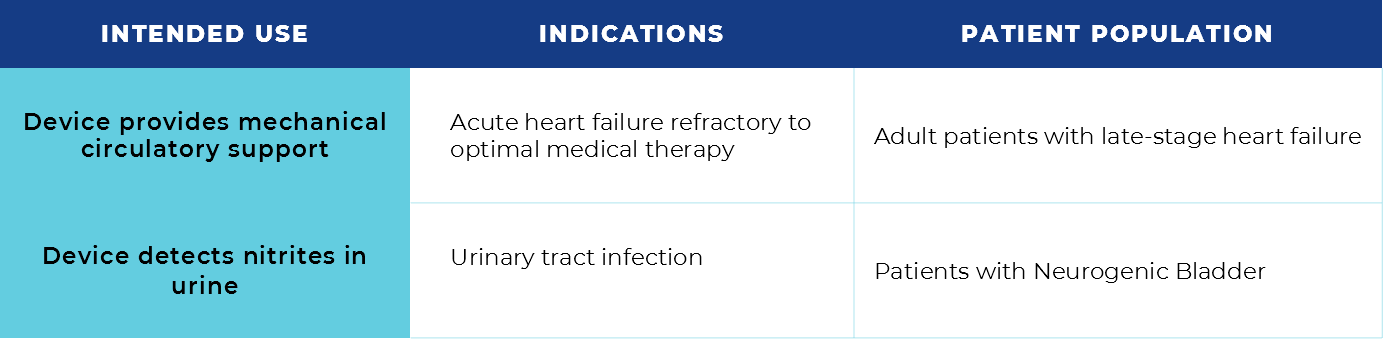

The first step of design control is determining User Needs as these will directly influence all subsequent parts (think of these as your main idea or your thesis of your essay). User Needs can come from various sources; however, a couple of key areas that must be clearly identified and determined are the intended use and indications for use. Because it’s not always clear, the difference between these is explained below.

- Intended use covers the general purpose that the device serves to fulfil.

- Indications for use covers medical conditions, abnormalities, or diseases that the device will diagnose, prevent, cure, or mitigate.

Further context can be added to the statement to include the patient population as well.

In other words, the intended use is the objective of the device, while the indication for use describes the disease or conditions that the device will diagnose, prevent, cure, or mitigate. And patient population is the group of people for which your device is intended and/or indicated.

Here are a couple of examples to elaborate on the difference:

For more information refer to 21CFR 801.4 and 21CFR 814.20.

Design Inputs

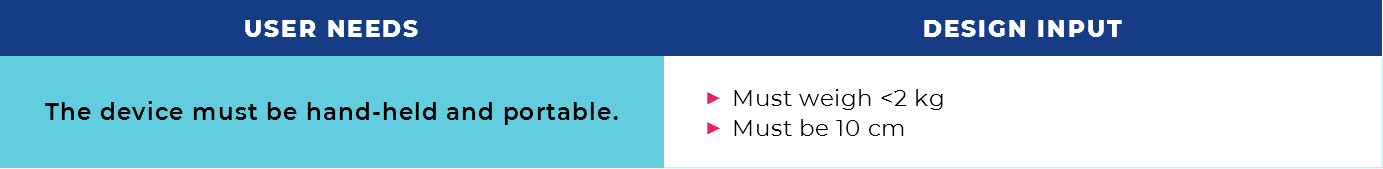

Once you’ve generated all of your User Needs, it’s time to determine design inputs, which will ultimately dictate the overall design. Design inputs are measurable design features that are intended to capture all functional, safety, and performance requirements.

For instance, suppose a user must be able to carry a device through a hospital. The device then must be portable and easy to lift and hold. So, the device’s weight and dimensions are going to be important to meet this User Needs. For example, for a portable device, the device can’t weigh a ton or be too awkward or cumbersome in shape. We may then say the design input is: “the device shall weigh no more than 2kg.” And with regard to shape, perhaps “the device must be 10cm in height.”

Something to notice here: One User Needs maybe associated with multiple design inputs. Other features such as adding handles or wheels to improve portability can also be part of the design input.

The table below shows an example of how these may translate into a design matrix.

Design inputs may come from places other than User Needs as well. Some other sources include:

- Industry standards

- Guidance documents

- Past precedent (previously cleared products/predicate devices)

- Competitors

- Risk analysis

Also - when creating these inputs, it’s important to make sure the inputs have two characteristics.

- Clear and concise and

- Can be tested to Pass/Fail.

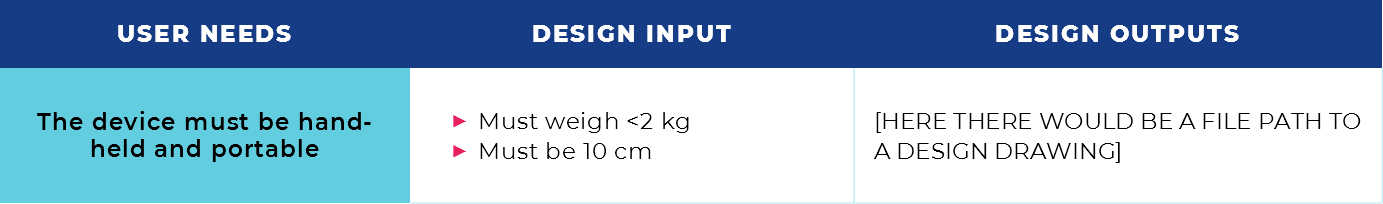

Design Outputs

Design outputs are the documents that show that the design inputs have been implemented. These documents serve as guidance for consistent production and assembly of future products. So, when you generate the finalized version design output records, you should be able to assemble the device with the same design, quality, specification, and functionality on consistent basis. Design outputs will include records such as:

- Drawing

- Design specification

- Manufacturing plan and instructions

- Component specification, and

- Production and assembly instructions.

For each record, the language must reference the acceptance criteria that is laid out in the corresponding design input. Continuing on with our example—if you specify in your design input that the device should be 10cm, then design output document must specify that the device is in fact 10cm, and your engineering drawings should indicate that.

Ideally, design output records will be generated so it allows for development of your medical device with the same quality and characteristics from scratch.

Adding to our example from before:

It is very important to differentiate between design output records and device master record (DMR) of which design outputs are a part. The FDA in 21 CFR 820.181 explains the purpose of DMR and the information that DMR must contain. We’ll cover DMR in much greater details in our future articles.

Design Verification and Validation

After generating all User Needs, design inputs, and design outputs, the design must be verified and validated. This is often referred to as “V&V. “But what does it mean? At this stage, you’ll need to establish that:

- You designed what you intended (Design Verification)

- Your design does what you needed it to do (Design Validation)

In more specific terms, Design Verification is in place to ensure that the design output can consistently meet the design input. Here, objective evidence, such as test reports, is often necessary to confirm that the device is able to satisfy the design input.

Design Validation, on the other hand, is in place to ensure that the final product can consistently meet all the User Needs determined in the first stage.

So, to put all this another way, design verification ensures that the product is developed correctly, while the design verification ensures that the correct product has been developed. For more information on Design Verification and Design Validation refer to future articles.

Design Reviews

Design reviews take place at the various stages of the design control procedures. During the design review meetings, the progress made on each of the design stages is reviewed in detail to make the device is safe and design control parameters are being implemented consistently and properly. Due to the iterative nature of the design process, the data gathered from one stage of the design may feed into the previous stage, so design review meetings are essential to identify and discuss new discoveries and implement associated changes.

Design Controls Process Overall

Keep in mind that the design controls process is an iterative process, and the data gathered from one phase can feed into the next or previous phase; therefore, you want to keep precise documentation and control measures to capture all the activities properly. The documentation must identify and describe all the parameters that can impact the device design. At the end of each stage, all the generated documents must be reviewed, and approved according to the organization’s approval matrix. It is very critical for every medical device company to follow the design control procedures set by the FDA (21 CFR 820.30) and properly document all of their activities accordingly.

Next we'll dive into Risk Management. Interested in more information? Chat with our team!

Source:

FDA Design Controls Presentation

Design Controls - Requirements for Medical Device Developers (GlobalCompliance Panel)

8 Questions That Define Your Medical Device User Needs (Greenlight Guru)

The Art Of Defining Design Inputs And Design Outputs (Greenlight Guru)